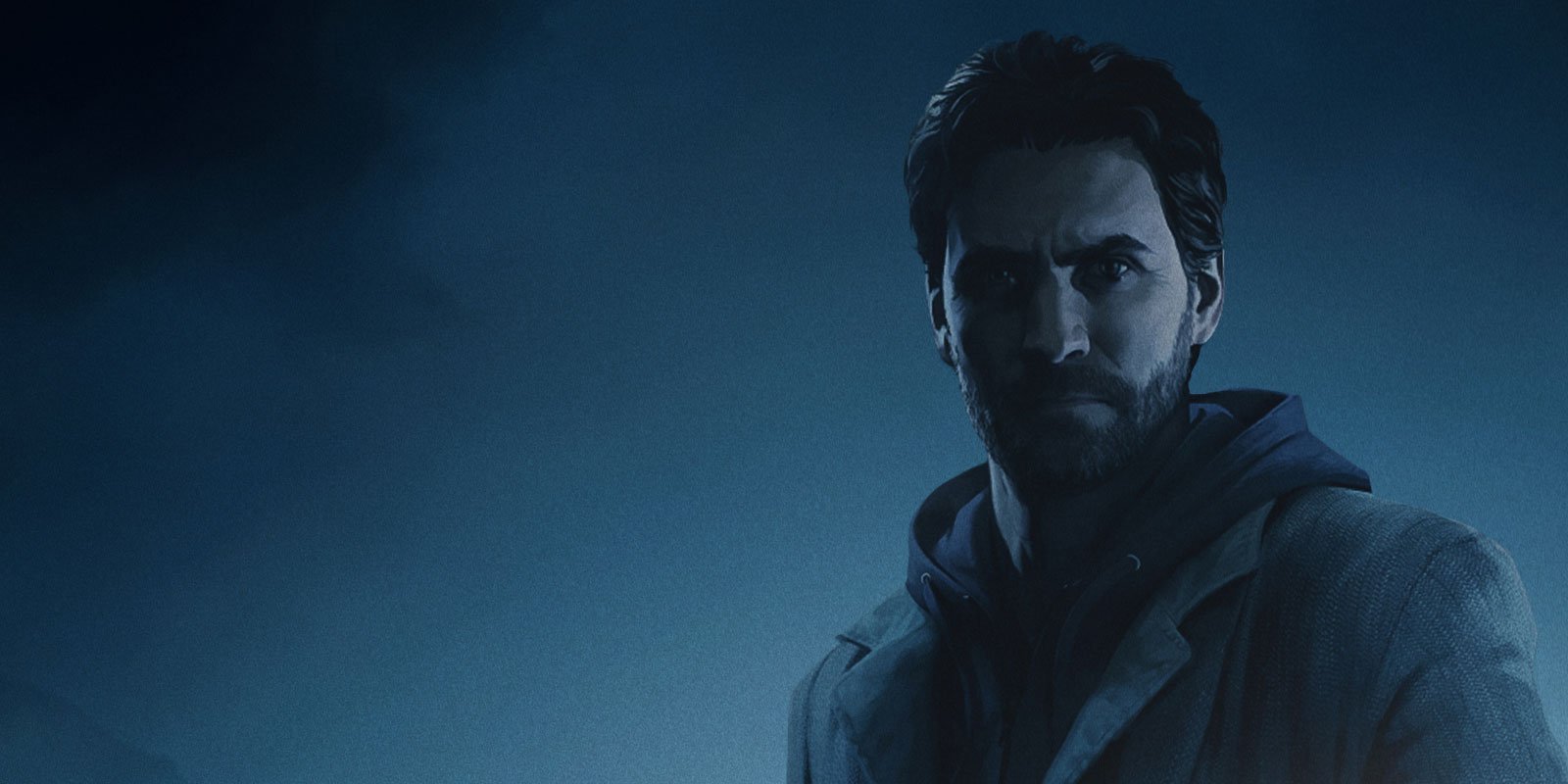

Alan Wake: I See A Darkness

In the second of three editorials leading up to Halloween, our resident Director takes a trip to Bright Falls to write about Alan Wake, and how the Remedy Entertainment cult classic gives the player a glimpse into the horror of creation.

For a good portion of my life, I was deathly afraid of the dark. There was something about the idea of anything being present in the black nothingness that you could never quite make out that just made my blood chill. For an embarrassingly long amount of time, I wouldn’t be able to go to sleep without the use of a night light. It wasn’t until I started sleeping together with my lovely fiancé (or as the Renegades know her, the incomparable Kay-Rah), as she is all the light I need...

I’ve never kicked the fear of the darkness completely though… even now, whenever I go outside at night, or I drive home from work around the stroke of midnight, or even when I’m gearing up for bed and I swear that I hear the slightest creak in my dingy one bedroom apartment, I always tense up. I walk with a scared spring in my step, or I play some music to drown out my thoughts on the road, or I even go through the effort of making sure the doors are closed even though I’ve done it god knows a handful of times and I know they’re locked. It’s compulsory, I know. But even though I’m damn near my mid 20’s, in the darkness, I’m still a kid.

Maybe that’s the appeal of horror; of writing about horror in general. Being able to not only confront your own fears by putting them to pen and paper for others to peak into your psyche, but also being able to control them. I’ve recently started reading Stephen King again (aside from the short story Rest Stop that I adapted as a short film, and the mini-series Kingdom Hospital, I hadn’t read a good deal of his fiction, only seen his adaptations), and I’ve been playing a lot of horror games, and I’ve been slowly building up a resistance to horror. Before, I would never want to step foot into that genre for as long as I could help it, but the month of October was like a full moon to me, and it made me want to explore the genre in more ways that I ever cared to attempt in the past.

Like a kid going from the shallow end of the kiddy pool, I swam to the rougher waters where everyone was already at. Some of these experiences you’ll read about later on… but in my journey, I ran into a ghost from my past. A lost soul, a regret of mine that I carried from 2009 all the way to now…

This year, I finally played Alan Wake.

I’ve never been a stranger to Remedy Entertainment, and by extension the legendary storyteller from the Finnish development company: Sam Lake. Although my first exposure to their creations was the threequel to the iconic noir action series Max Payne by Rockstar Studios, I quickly sought out the first two installments in the series that were by Remedy, and I immediately spotted a difference in the storytelling. If Max Payne 3 was more hardboiled like a Shane Black or Frank Miller joint, the first two were more evocative of Brian Garfield novels and the Parker stories by Richard Stark (the pseudonym for Donald Westlake). They were dreary, dreamy, and disturbing nightmares from a man who is haunted by the warmth he had cruelly taken away from him by a cold and uncaring world. The poetry of Payne’s narration felt like listening to a really thrilling pulpy paperback, and the aesthetic of New York during the winter is the perfect visual metaphor for how our tortured protagonist was and of how dead feels on the inside. The nightmare sequences would pop up in my head at the worst times when I would be trying to do school work — I will never be able to forget the sound you hear when you’re trying to walk through the blood trail maze in the black sea of nothingness, and you fall down into the abyss, with only the droning echo of Payne’s child’s cries ringing in your ear before you respawn.

I unfortunately wasn’t able to play any of their other games. Quantum Break and Control I’ve heard are great games, and I may even pick them up at some point in the near future. But the one project that spoke to me more than Max Payne… was one I remember reading a preview for in Game Informer magazine in the late 2000’s.

Alan Wake was always going to be a curiosity for me. It felt like a horror game, but from a much more approachable lens of a third person action shooter that Remedy was known for. The graphics at the time were unmatched (this and Heavy Rain were the peak of realistic graphics in my young mind… foolish me), and the idea of playing as a writer was something very intriguing to me. I was fully prepared to step outside of my comfort zone in video games, and give this one a fair rent from the local Blockbuster or Hollywood Video (yes, that’s how old I am).

Then… I didn’t. I’d call it releasing in the wrong place at the wrong time. You may not remember, but 2010 was perhaps one of the biggest years of gaming. There were such seminal classics as Mass Effect 2, Super Mario Galaxy 2, Fallout: New Vegas, God of War III, and in the same month as Alan Wake, we had the masterful Red Dead Redemption. It was a great year for games… but Alan Wake just fell to the wayside, left to be swept up in a sea of darkness that would keep it held captive in a dark prison of video game obscurity for the rest of its days…

… but then something magical happened. During the Sony State of Play on September 9th, a special trailer played, courtesy of Remedy Entertainment: Alan Wake, after 11 years of silence, was getting a remaster for the next generation of consoles, JUST IN TIME for the Halloween spirit! It was as if we all picked up a remnant of the past, and we brought back an old friend who had never found his way home.

This felt as good of a time as any to finally sit down and play the game for the first time… but sure enough, before I got a chance to play the new Remaster, I had a very close friend hand me his personal copy of the Xbox 360 version.. and while I could’ve forked over the cash to get the modern version with all the DLC intact, as I gripped the lime green cover for the game in my hands, I felt this child-like rush inside me, where almost as if I was on autopilot, the game was already inserted in my old Xbox 360 Arcade Edition.

After 11 years of wondering what the game would be like… I was finally going to take that trip to Bright Falls.

A week later after meticulously scrounging the moonlit outskirts of Alan Wake for every last coffee thermos and manuscript page, I finally came to the end credits of the game. It was a helluva journey that brought me back to the nights where I sat on my Grandmother’s old recliner, curled up inside a blanket that is way too small for me nowadays, watching Kingdom Hospital and having nightmares about creatures that I could swear I saw moving in the darkness. Everything about this brought such a child-like wonder in a grown up setting that I felt genuinely moved by the final product, even if I felt the ending left me very cold.

It’s such a simple gameplay set-up. Having just played Silent Hill for the first time (more on that in a future editorial), I had grown used to roaming around a small town where secrets were sealed away in the bricks… but there was something unique about Bright Falls and Alan’s journey to find his wife.

I screamed in horror. I found myself twitching the control stick to aim at trees that I swore moved just seconds ago. As the screen would start to be consumed in darkness and the bright safety net I held in my hand started to dim more and more, my heartbeat would echo louder and louder until I ran promptly in the opposite direction. The darkness was everywhere and nowhere, and there were times I was a bit too liberal with my ammunition. The mechanic of literally fending off the darkness by weakening it with light is such a brilliant concept that immediately reminded me -- of all things -- of Luigi’s Mansion for the Nintendo Gamecube. The trigger memory of learning how it takes one really good shot to the head to knock out weaker enemies, but aiming anywhere else will eat up at least two bullets of my revolver, started to kick in as I started to press on… but almost as soon as I felt safe with the game, they’d take away the guns and have you rely on flares.

The thrills were so exhilarating; but the chills came from the story.

From the very first manuscript page, you will suddenly feel the compulsory drive to find every single page you can find. With Alan’s wife seemingly missing, and the darkness’s strength only getting more and more overwhelming, any peak into the future is more and more welcoming. But as the story starts to progress, you start to realize the darkness isn’t just from the town… but it could also be an extension of Alan.

Perhaps I should finally explain what Remedy has cooked up in the kitchen. Alan Wake is a crime writer with James Patterson levels of fame, taking a vacation to the small mountain town of Bright Falls, Washington. It’s meant to be a small bit of R&R until his wife Alice suggests he could maybe get some writing done in town. Wake is clearly against it, due to his own bout of writer’s block, as well as reeling with his own issues of alcohol abuse. After settling in to the cabin at Cauldron Lake, and after a little spat about the writing problems, Alice is suddenly dragged out of the house and sent into the lake. When Alan dives into the water, he suddenly wakes up after a car crash, and finds a page from a manuscript he seems to have written recently, detailing events that have either happened, are happening, or are going to happen. As he makes his way through the woods, he finds that dark creatures he had nightmares of are coming to life and taking control of the locals of Bright Falls… but when he gets the police to hear him out, it turns out he’s lost a week of his life, and a guy calls his number, claiming that he has kidnapped Alice, and won’t give her back until Alan hands over the rest of the novel.

It’s a lot to take in, but the game does a great job of having you lose your sense of reality as Wake starts to struggle with what is real and what isn’t. Between the entities chasing him in the woods, the world’s most cartoonishly evil FBI agent, and the never-ending showers of birds that cut through the player like razors, it feels as if the world is against Wake… but as you start to uncover more secrets of the town, it appears the real villain might be lying within.

It probably won’t come as a shock to you, dear Renegades, when I tell you that this game’s narrative was inspired by the works of Stephen King and Twin Peaks! I know! I know! Hell, the character of Alan Wake wouldn’t sound out of place in the paperbacks of a King book you’d find at your local Walmart. King’s work seems to have seeped its way into most psychological horror based games since the days of Silent Hill on the PS1.

However, while most people look to King’s use of horror set pieces and small towns as a blank canvas for artists to create their own homages, what a lot of people don’t pick up from the King of Horror is how he crafts his narratives based on the character’s own psyche’s. But Alan Wake, like some of the best homages to his works, is one that understands this fundamentally and bakes it into its gameplay.

The fear of the darkness is at once metaphorical and thematic: it makes Alan (and by extension, the player) empathetic to Alice’s fear of the dark. You scrounge for extra batteries to be able to keep your flashlight shining bright, and each variation of the torch helps you breathe a little easier as you fumble around trying to ignite generators. When you step into the light, not only does it replenish health, but it also makes all of the Taken vanish back into the darkness where they belong.

But I did say it’s thematic too… and it forces the player (and by extension, Alan) come to terms with the inherent darkness inside ourselves and the character we’re playing. When we look at the taken, more often they are exaggerated caricatures of the people Alan has met over the course of the game’s chapters. From Wake’s first arrival in Bright Falls up until he gets committed to the care of Dr. Emil Hartman, he isn’t exactly kind to most of the denizens of the town, and in fact looks down on the humble citizens more often than not. The descriptions of the characters Wake writes in the manuscript are unkind at best and harsh at worst, and the conversations he has in the game go about as well as engaging in political conversation with a German Shepard: all bark, with nothing sinking in.

But that’s just considering how he looks at the town… but what about Alice? After all, she’s been gone this whole time, and when the blackmailer asking for the manuscript ends up being a red herring, it leaves you to wonder who (or what) had taken her?

As it turns out, the town is more or less a supernatural entity that feasts on creativity, and makes art come to life through the artist. From the aging rock band themed after the Gods of Asgard, to the poet Thomas Zane, everyone who makes art in the town of Bright Falls ends up bringing about darkness and evil that only wants to feed on those who have created or want to create until it swallows them whole; taking away that last spark of sanity to break free. Anything you’d want can be made real… but it comes at a price, as always.

Alice was taken from the lake, and - like Zane before him - Wake is forced by the entity to create a novel by which it can escape, luring him with the promise that he can bring Alice back. But as Wake gets further and further into the story, not only is he losing his grip on the progression of the plot, but he also faces the dark side of himself. While the entity did take Alice away from Alan, he had brought it on himself through the cruel treatment of the people closest to him.

The cruel comments about the townsfolk; the neglect and verbal abuse towards Alice; the disrespect of Barry Wheeler (his agent); and the disregard of his own work and his health: it’s a hell of his own making, one that he needs to come to terms with at the end of the story as he reaches the end of WRITING his story.

It’s a sad reality that all writers have to face (myself included) when it comes to crafting fiction: how personal and how dark we are willing to go into. We are our own worst critics at the end of the day, and as bad as people may find you, it’s almost assured that you can say a helluva lot worse. When taking a look inwards when using your imagination, you peak into the worst parts of yourself and mine it for entertainment (or worse, content). Along the way, you could hurt the people closest to you, as well as irreparably damage the memories you’ve made along the way. From the mind to the page, actions and words are as solid as a mound of clay, continuously restructuring until they reach a more digestible execution.

It might sound absolutely pretentious at the end of the day, and it might not even be a part of the main idea behind what Lake and co-writers Mikko Rautalahti & Petri Järvilehto were going for when crafting the narrative and scenarios of the game, but what struck me more than anything with Alan Wake was how much this game portrays the inner struggle of creation. How as coveted as creativity is… like anything, it can be corruptible and fester into a poison that slowly infects everyone around you.

How far are you willing to go to create? And are you willing to change yourself for the people you love?

These are the questions that hover over Wake at the end of the game. When Alan is trapped in the darkness, having to literally construct the world around him by shining a light on his own words to bring them to life (the moment that inspired this very editorial), he finally arrives at the cabin that used to reside on Cauldron Lake in order to finish the manuscript. What started as a way to save his own wife and even honor her by finally writing for her, it’s too late for him to fix everything he had done before their arrival, to take back all the words he had said, and to undo all the actions he inflicted from his drunken stupor as shown from the flashback before the last episode of the game. He does what is expected, and brings the tale to a close.

As the game ends, Alan finishes the manuscript by setting everyone free, but leaving himself alone in the darkness with no way of rewriting himself back into reality, ending with the lines, “It's not a lake, it's an ocean.“

At first glance, this feels very cold and unsatisfying as an ending; upon reflection, it’s unbelievably bleak and hopeful all at once. Alan was unable to save himself in time, and as a result is stuck in a prison of his own design… but there’s a hope that the people around him are able to live on, that the sources of light in his life are able to shine on and shine bright. It’s self-destructive, but calls back to the darkest of concepts lifted straight from the pages of Stephen King: we are our own worst enemies.

In the end, it made me realize that the darkness I was so afraid of isn’t in the world around us… but inside us. Because while you might not realize it right away, what’s inside isn’t as small as you think. It’s not a lake, it’s an ocean. Will you find your lighthouse before it’s too late?

Welcome back to another episode of the Renegade Arcade Reloaded! This time around, Neoplasmic and Organoid Zero are joined by our wonderful friends and contributors, Rynkoth, Red, and Rogue, also known as the R Squad (I just made that up), as we discuss the best games of 2024, including Final Fantasy VII Rebirth, Metaphor ReFantazio, Tekken 8, Black Myth Wukong, Stellar Blade, Marvel vs. Capcom Arcade Classics Collection, Infinity Nikki, Marvel Rivals, and much more! Click that button to listen in and don’t forget to follow us on Spotify!